In March, three members of The Whistle team - Giles, Isabel and Ella - headed to San Francisco for RightsCon. This annual conference is the biggest get-together of those working on the intersection of technology and human rights: human rights researchers and advocates, lawyers, academics, tech company representatives, and government officials.

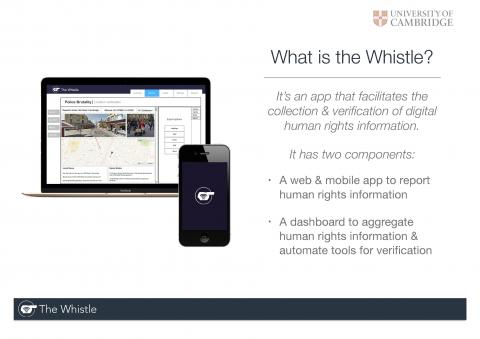

We gave a lightning talk on The Whistle in the conference Demo room - and here’s the slides. They’re good for a quick overview of the aims of our project and the collaborations we’d like to make.

What is verification? Verification is an important part of turning human rights information from the subjects and witnesses of violations into evidence that can be acted upon. Verification involves a set of beliefs and practices that we draw upon to assess the extent to which we think information is true.

How is verification done? By cross-checking the information against other sources and with other methods.

This is why we have seen so much excitement about digital human rights information from civilian witnesses in media, academic and practitioner spaces. It allows fact-finders to get digital reports of human rights violations from hard to reach places, and allows civilian witnesses to document these events as they unfold.

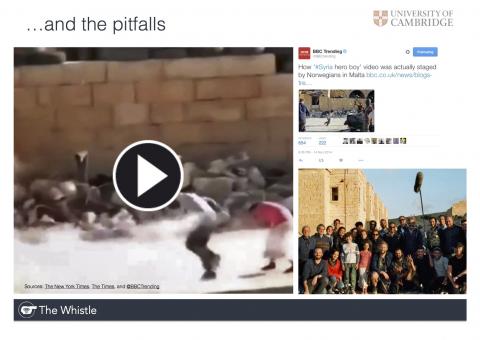

At the same time, however, the stakes are high in terms of getting this type of information wrong. This is in part because it is relatively manipulable. You may remember, for example, this viral Youtube video called ‘Syrian Hero Boy,’ which allegedly showed a boy dodging sniper fire to rescue his sister. The BBC quickly discovered that it was staged - filmed by a Norwegian director with child actors on the set of Gladiator in Malta. (Of course, this is a more egregious example; it is far more likely for real events to get recycled out of context for propaganda and other purposes.)

Fortunately, the number of tools to support the cross-checking of digital information is proliferating. We have tools to cross-check location and time, to unearth details of the source’s digital footprint, to trace back the provenance of the information, to extract the metadata of the information, and so on and so forth. Phew, that’s a lot of tools!

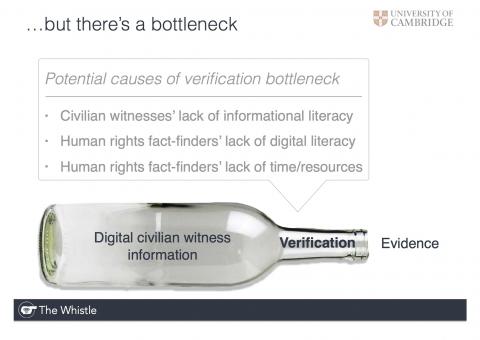

Despite these tools, civilian witness information is not being used as human rights evidence as much as one might expect.

Where’s the bottleneck from? We’ve identified at least three causes we want to address - though we know there are more.

First, civilian witnesses’ lack of digital and information literacy: We have heard from fact-finders that civilian witnesses do not necessarily know what metadata is or that they should include it with their information - whether this means panning the horizon for landmarks or turning on geolocation features. The paucity of metadata in their information makes it much harder for fact-finders to verify it.

Second, human rights fact-finders’ lack of digital literacy with respect in particular to digital verification: Though the fundamentals of verification remain the same, the tactics and tools for verifying digital information are new and changing rapidly. This complexity might be discouraging fact-finders from turning to digital information from civilian witnesses.

Third, human rights fact-finders’ lack of time: Even for those who are up to speed on digital verification tools, this process takes time. Individually, each of those tools may only provide a limited indication - if anything - about the veracity of the reported information, and opening up each tool and entering the information to be cross-checked is not only time-consuming but a nuisance.

And the question is, in the context of what one journalist called a ’big data problem’ in Syria, and a limited number of hours in the day, who gets heard by fact-finders? We are particularly worried - given the complexity of verification and the time pressures of fact-finding - that those who are easier to verify are more likely to be heard. Those harder to verify (because they don’t have the information literacy to make good quality information, or because they don’t have the digital footprint needed to verify their identities) may be less likely to be heard. It is precisely these civilian witnesses - those on the low end of the resource spectrum - who may be most likely to need human rights mechanisms.

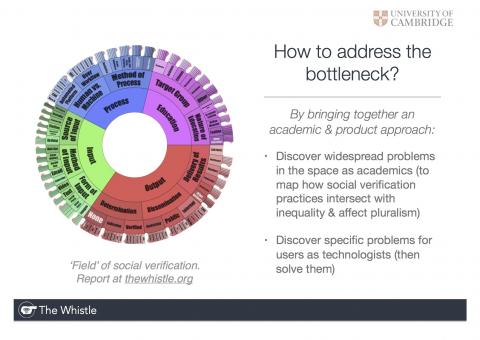

As an academic project, we are interested in the emerging practices around the verification of digital information from civilian witnesses - not just because of its promise, but also because of its problems.

We have a particular focus on how these practices intersect with inequality and have consequences for pluralism (if you want to know more, our research, including this map of the digital verification field, are available here under ‘Research’).

We know that human rights organisations share our concerns with inequality and pluralism, and so - in our dual role as technologists - we are entering this space to help ease the bottlenecks.

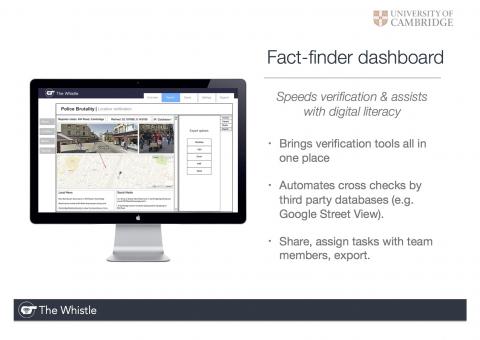

Which brings us back to The Whistle. We are designing The Whistle to address these bottlenecks on two fronts. First, The Whistle will have a civilian witness interface that addresses the first bottleneck via increasing the quality of reported information. Second, it will also feature a dashboard for fact-finders to aggregate human rights information and automated tools for verification - which should address fact-finders’ potential lack of digital literacy and time.

The civilian witness interface increases the quality of reported information in 3 ways:

First, by prompting witnesses to provide more metadata as they enter their reports;

Second, by educating witnesses about what data is most helpful and why, in order to boost their information literacy for the future;

And third, by directing witnesses to further resources on security, human rights evidence, and human rights mechanisms.

The dashboard, mocked-up here, speeds verification in a number of ways. It collates verification tools so they are all on one screen rather than in innumerable browser tabs. It automates the cross-checks by populating third party databases - such as Google Streetview with the reported location. And it will allow fact-finders to share information with team members, to assign tasks, and to export reports.

We’re currently in the research and design phase, funded by the ESRC and by the EC’s Horizon 2020 programme, and with one collaborator, WikiRate, which aims to improve corporate accountability, including through workers’ reports of abuses, which is where The Whistle comes in.

We’re actively looking for collaborators. We have already been talking with fact-finders on the ground, but we want to talk to more of you for input on usability and workflow. We are also interested in establishing test cases where we would collaborate with a fact-finding NGO to get feedback both from the test organization and from the civilian witnesses submitting reports. Furthermore, we would like to consult with tech companies on the design of The Whistle.

In sum, we hope that by speeding verification, The Whistle expands the pluralism of voice in human rights fact-finding. Thanks, and we look forward to hearing from you!